You've never heard of Lucien Rosengart (1881 to 1976)? Most people have. Even in France, where Rosengart - a highly decorated commander of the Legion of Honor - once employed up to 4,500 people, he is virtually unknown today. So who was Rosengart?

The fact that this impressive personality has not long been forgotten is largely thanks to a collector and his life's work. Consequently, there are two stories to tell here: that of a brilliant inventor and industrialist and that of a dedicated collector and preservationist.

Fate: From the idea to the museum

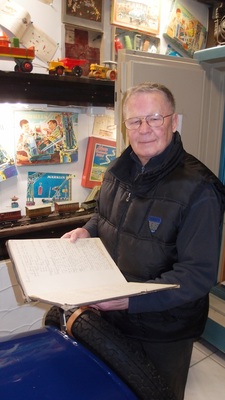

Let's start with the more recent story. Or rather: with an original idea. In 1980, Karl-Heinz Bonk (born in 1939) from the Rhineland decided to buy a car that was as old as he was. He already owned a few classic cars at the time, such as a Citroën 11 CV Traction Avant, also known as the "gangster limousine".

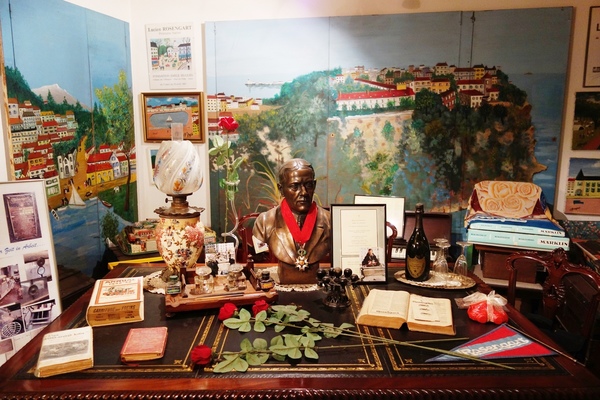

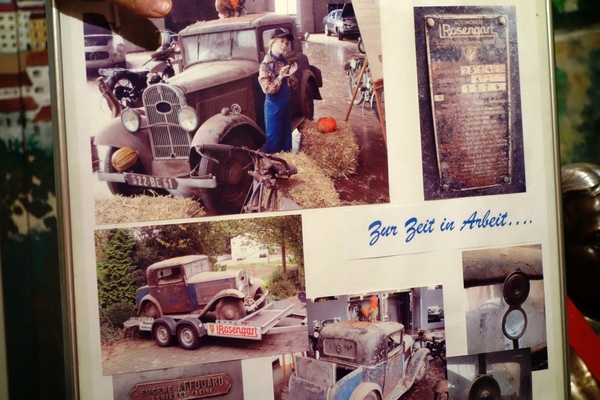

By chance, he finds a small car of the year he is looking for and buys it. It was a Rosengart. He had never heard of this make before. But was it really just a coincidence or fateful coincidence? After restoring the car with the help of his friend Manfred Petak, he couldn't get away from Rosengart. Today, he owns 32 cars of this brand and has collected everything he can about Rosengart in 41 years. He and his understanding wife Erika have been running the private Rosengart Museum in Bedburg-Rath for 26 years now. It is the only one of its kind in the world.

There are 30 restored and roadworthy vehicles there and the museum director can tell a story about every car. For example, the 1931 LR 44 "Plattformer" (LR stands for Lucien Rosengart), a small truck that was left to rot in a Belgian stable. Today, the car has been perfectly restored and can be seen in the museum along with the accompanying documentation.

Opposite is a dainty racing car, an LR 4 Spezial. "I took part in the historic Klausen race with it," Bonk remarks rather modestly. And then he points to the elegant black LR 505 Supertraction Aérodynamique limousine from 1934 with a strikingly curved rear end. "There is only one of this type left in the world and you can hire it for weddings". Incidentally, it is the only car he has given to someone else after a bad experience.

Beautiful details

Visitors should definitely take the time to look at the details of the museum. There are contemporary enamel signs and toys in all shapes and sizes to discover. It is also worth taking a close look at the cars on display.

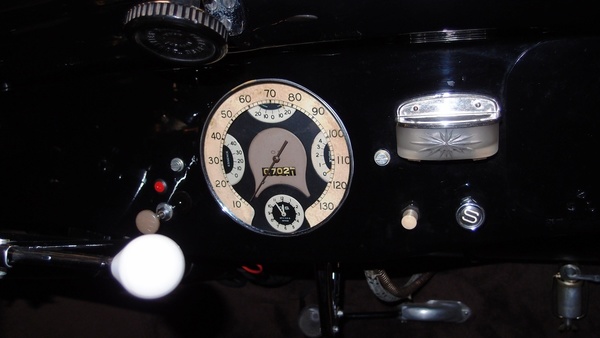

"Rosengart was the first car manufacturer to think about women," says museum director Bonk. The cars had a place for make-up utensils, as well as practical storage nets above the windshield and a glove compartment - which was by no means standard at the time.

Fans of Art Deco automobiles will also get their money's worth, even if a Rosengart from the late 1930s does not look as opulent as its contemporaries, the Panhard Dynamic or Delahaye 135 Roadster. But: headlights, door handles and hinges, the curved fenders and bumpers, sweeping chrome strips and, last but not least, the dashboards - they all breathe the spirit of that era.

And the Rosengart company logo can also be found in places where you wouldn't expect it. Finally, there is a jumping horse to discover as a radiator grille. It is older than the famous rearing "cavallino rampante" from Italy and only exists twice in the world.

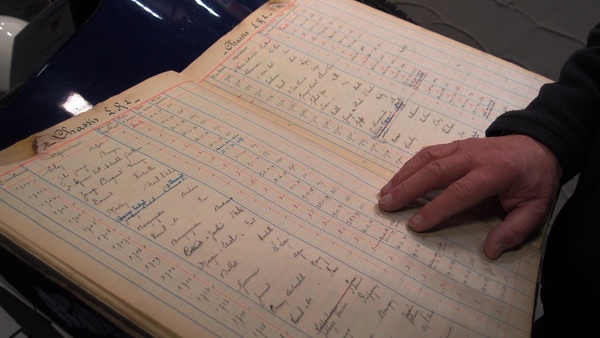

Unique archive material

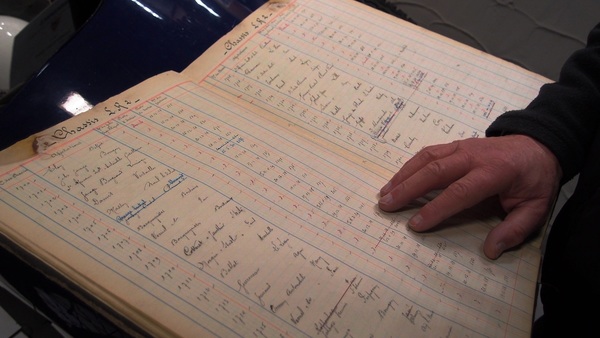

Let's turn to other rarities in the museum: there are patent certificates and original documents in abundance, even the handwritten (!) books on the delivery of all Rosengart cars with 4 cylinders produced since 1928, the so-called "chassis books", are safely stored there.

"I am fascinated by Lucien Rosengart's life's work," admits the museum director. And admits that he is probably also a little obsessed, as he adds: "I'm always on the road a lot and cover around 50,000 to 60,000 km a year."

He traveled to Paris six times alone until he finally found Rosengart's grave at Montrouge cemetery to place a memorial plaque there. For decades, he has been tirelessly making contacts, interviewing contemporary witnesses, acquiring and exchanging vehicles, rare spare parts and anything else he deems worth preserving. Bonk pursues his goals tenaciously, often using only gestures in his negotiations. But what he ultimately gathers makes Rosengart appear to be an ingenious and, above all, versatile person. And that brings us to the second story.

Lucien Rosengart, a bustling genius

Lucien Rosengart was born in 1881, the son of a manufacturer of precision mechanical equipment. He only attended school for six years and then worked in his father's company. He founded his own company in 1903, producing screws, nuts and grease nipples for industry. And he invented the stainless steel screw. Although it is indispensable for the Paris metro, it only earns him ridicule.

He develops a hand flashlight ("Dynapoche") that works without a battery and supplies the French car industry. During the First World War, he develops special grenade fuses: instead of just one part, he manufactures four, thereby speeding up the production process enormously.

In 1918, he is a major industrialist and employs 4,500 people. And he is socially committed: some of his employees are disabled people, for whom he provides special tools. This was not a matter of course at the time.

A year later, he was asked by André Citroën to save his ailing car factory - today, Rosengart would be described as a management consultant. Equipped with far-reaching powers of attorney, he managed to raise the necessary 20 million francs within one night. He was also involved in the development of the Citroën 5 CV Trèfle, which Opel strongly imitated with its Type 4 PS ("tree frog") - to put it mildly - but painted green rather than yellow. According to one interpretation, the expression "the same in green" goes back to this. During his time at Citroën, Rosengart also launched publicity campaigns. At the turn of 1922/23, for example, he crossed the Sahara from Algiers to Timbuktu with five tracked vehicles.

At the same time, he continued to work as an automotive supplier. "There isn't a French vehicle that doesn't have my company's products in it," he is said to have remarked at the time.

At the same time, he invents a record player drive. The corresponding patent certificate from 1923 calls it an "electromotive friction drive for speaking machines" in bumpy official German!

He also developed the table football game, although this was not entirely uncontroversial.

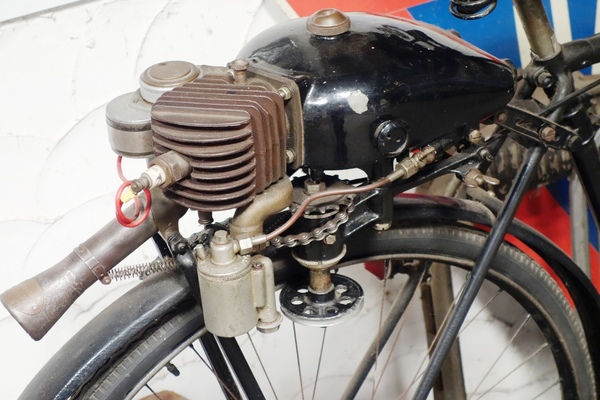

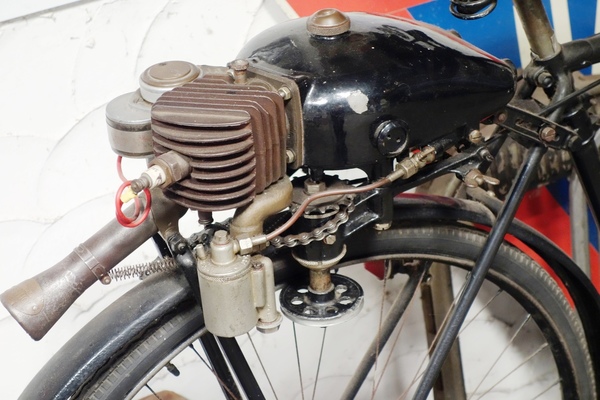

From 1923 to 1927, he worked for the automobile company Peugeot in order to save it too. Peugeot - which was split into several locations - was also in urgent need of restructuring. However, this job was somewhat tricky, as it also brought Rosengart into conflict with Citroën, which had previously been rescued. Incidentally, while still working for that company, he developed the "Moteurcycle", an auxiliary motor for bicycles. As a reminder: decades later, something similar came to us from France as the Velosolex. At the same time, he also developed a two-cylinder, two-stroke engine as an outboard motor for motorboats.

Rosengart as an automobile manufacturer (1928 to 1955)

Rosengart began producing his own automobiles in 1928. After a thorough market analysis, he defined three criteria for his cars: they had to be economical, low-maintenance and, above all, affordable. As a result, he produced simple small cars that could even be purchased in installments. Initially, he produced the British Austin Seven under license. Others were also doing this at the time, such as the Dixi company in Germany, which was later taken over by BMW. Around 107 cars are built under the name LR 1. Rosengart purchases the first 100 engines from Austin, after which he builds them himself and develops them further over the years.

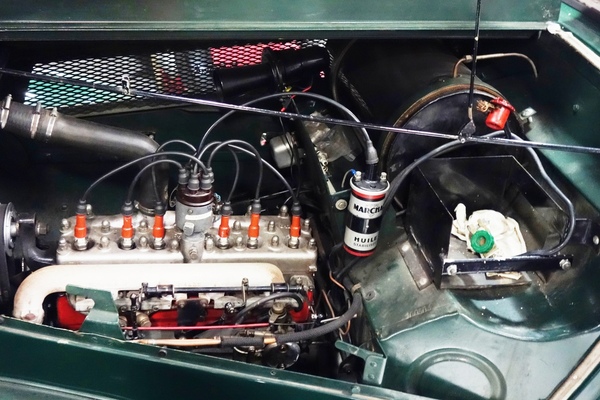

Just one year later, he introduces his own body variants. The car, produced in around 6853 units and seven body styles, is now called the LR 2. It is equipped with a 4-cylinder, 4-stroke engine with 747 cc, which produces 13, later 15 hp. It consumed only approx. 6 liters of fuel per 100 km. According to the production register in the museum, several examples were delivered to BMW.

One anecdote should not go unmentioned, as it leads to a new automobile design: in 1929, Rosengart met a beautiful woman getting out of a large Packard in front of the "Maxim's" restaurant in Paris. Lucien wants to know why she is driving such a truck. She asks Rosengart, who is sitting in his little car, why he is making cars for children and playing with them.

In response, the industrialist develops a pleasing model with six cylinders and demonstrates it to the lady in question just six months later. Incidentally, she would become his third wife years later. In terms of automotive history, it is interesting to note that the engine of the aforementioned car - the LR 62 type, later built from 1934 to 1935 - was created by Rosengart simply extending the Austin 4-cylinder by 2 additional cylinders and adapting the crankshaft. This gave the small six-cylinder engine a record-breaking displacement of just 1097 cc!

From the 1930s onwards, Rosengart cars took part in long-distance races to prove the durability of the cars. In 1930, private driver Francois Lecot undertook a record drive of over 100,000 km - without the support of Rosengart - by covering the distance Lyon-Bourg-Dijon in 111 consecutive days without any problems. However, as this achievement was disputed, it was repeated two years later - this time under the supervision of a French automobile club.

In 1932, Rosengart visited the Adler company, which was the third-largest car manufacturer in Germany at the time, and acquired the license to reproduce two models. The LR 505 Supertraction, based on the Adler Trumpf and built from 1934 to 1936, is a very modern car and is already equipped with a 12 V electrical system. Remember: this was not a matter of course until the 1960s!

At the same time, Rosengart was the first - even before the Citroën Traction Avant(!) - to launch a front-wheel drive production car on the French market. From 1935 to 1948, he built the successful LR 4 N2 model in many variants. A total of around 22,636 units of this model were produced. From 1937/38, it was given a characteristic, curved "fencing mask" as a radiator grille. A new model was produced from 1939: the LR 539 Supertraction. This is a large car with the drive technology and engine of the Citroën 11 CV; the bodywork was designed by a Rosengart designer named Robin. The convertible in particular is very attractive.

During the war and the Vichy regime in France, car production came to a standstill. Rosengart had to go into hiding in the south of France because of his Jewish ancestry. His future wife manages to pass him off as her uncle and hide him on a previously acquired estate. He therefore did not emigrate to the USA, as is sometimes claimed.

New start and retreat

After the war, Rosengart briefly served as mayor of the small town in the south of France where he had gone into hiding. He undertakes a trip to the USA to make business contacts. When he returns to Paris, he finds his factory desolate. He launched the Ariette and Sagaie models through the SIOP company, which he had initiated before the Second World War, which is why "Rosengart SIOP" can sometimes be found as the manufacturer's name.

It is less well known that the body of the Ariette was designed by the later design pope Luigi Colani. This car with its modern pontoon style bodywork is somewhat similar in profile to the Gutbrod Superior or contemporary models from the Borgward Group. However, the Ariette was not a great success. It ultimately had the proven but now antiquated engine of the Austin Seven with 17 hp and was therefore inferior to the Renault 4 CV ("cream slice") in particular. The equally unsuccessful Sagaie had a 2-cylinder boxer engine from Panhard with 38 hp and a plastic body.

Although a few more prototypes were presented, largely based on the pre-war cars (including an eight-cylinder car with a Mercury engine, the "Super Trahuit"), 1955 was the final year of production. The factory buildings were demolished for the construction of the new city highway around Paris. Lucien Rosengart had already gradually retired from automobile production to begin another phase of his life. He was over 70 years old at the time and, according to estimates by Karl-Heinz Bonk, had produced around 100,000 cars. From then on, Rosengart lived in Switzerland and the south of France, where he owned real estate, and devoted himself to naive painting. His paintings, some of which are large-format and some of which are painted on cupboard walls, are exhibited several times. Quite a few of them can be seen in the Rosengart Museum. "I hope to be able to acquire more paintings," says Karl-Heinz Bonk.

In addition to his artistic work, Rosengart also continued to register patents. Throughout his life, he registered 132 of them. Even his death, which came at the ripe old age of 96, was somewhat spectacular. He did not die of old age, but of salmonella poisoning caused by spoiled ice cream.

What remains...

Time for a conclusion: Lucien Rosengart was undoubtedly very versatile and inventive. And without him - a little speculation is allowed - Citroën and Peugeot might not have existed for a long time. But that is only part of his CV.

So what is his significance as a car manufacturer? Certainly not in the glamorous. His cars were never as spectacular as those of other French manufacturers. Rosengart automobiles never played in the league of Talbot-Lago, Delage, Delahaye, etc., nor were they dressed by renowned coachbuilders. They were neither super sports cars nor prestige objects for the top ten thousand. This is probably why they do not play a significant role in today's beauty contests for classic automobiles. Instead, Rosengart built inexpensive small cars whose engines were ultimately all based on the 4-cylinder Austin Seven. He had therefore already achieved his declared goal of building cars for broad sections of the population in the 1930s.

He had less success with his larger cars, although these cars were progressive. Was it because they were based on third-party developments (LR 505) or third-party technology (LR 539)? The production figures for his post-war models are also modest. There was obviously no longer a market for his larger cars. It was no longer enough that the large LR 539 Supertraction Cabriolet in particular was visually very appealing, even opulent. But even those French car companies that had once produced the "Grand Routières" had to give up one after the other in the post-war period. Perhaps because the former wealthy clientele hardly existed any more.

But why was Rosengart no longer able to build on its earlier successes with its small post-war vehicles? After all, there was a demand for simple small cars in the first few years after the war. He certainly had strong opponents in this segment with Renault and Citroën in France and perhaps a more modern engine would have been helpful. Nevertheless, Rosengart did not fail as a car manufacturer, he just gradually withdrew from the business.

The expert Bonk reports that Rosengart himself advised a consortium that wanted to save the plant in Paris not to do so. Presumably he had simply lost interest in car production and wanted to move on to other things. His importance as a car manufacturer therefore ultimately lies in the fact that he produced affordable cars for broad sections of the population in the period before the Second World War.

If you add his many other activities, however, it is hard to explain why he is almost forgotten today. Karl-Heinz Bonk, who would like to take this opportunity to thank for his valuable information and evidence, wants to counteract this with his museum. "Perhaps Borgward will also be forgotten one day," he says somewhat melancholically at the end of my visit. But you can't take care of everything...

Additional information

The Rosengart Museum can be found at Lucien-Rosengart-Weg 1 in D-50181 Bedburg-Rath. It is open from March 1 to November 30 on Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays. Further information can be found on the museum website.

Those interested in Rosengart should also refer to the book by Josef Krings and Karl-Heinz Bonk on the Rosengart Museum, which provides 180 pages of information on the life and work of Rosengart and is available from the museum for EUR 23.80.