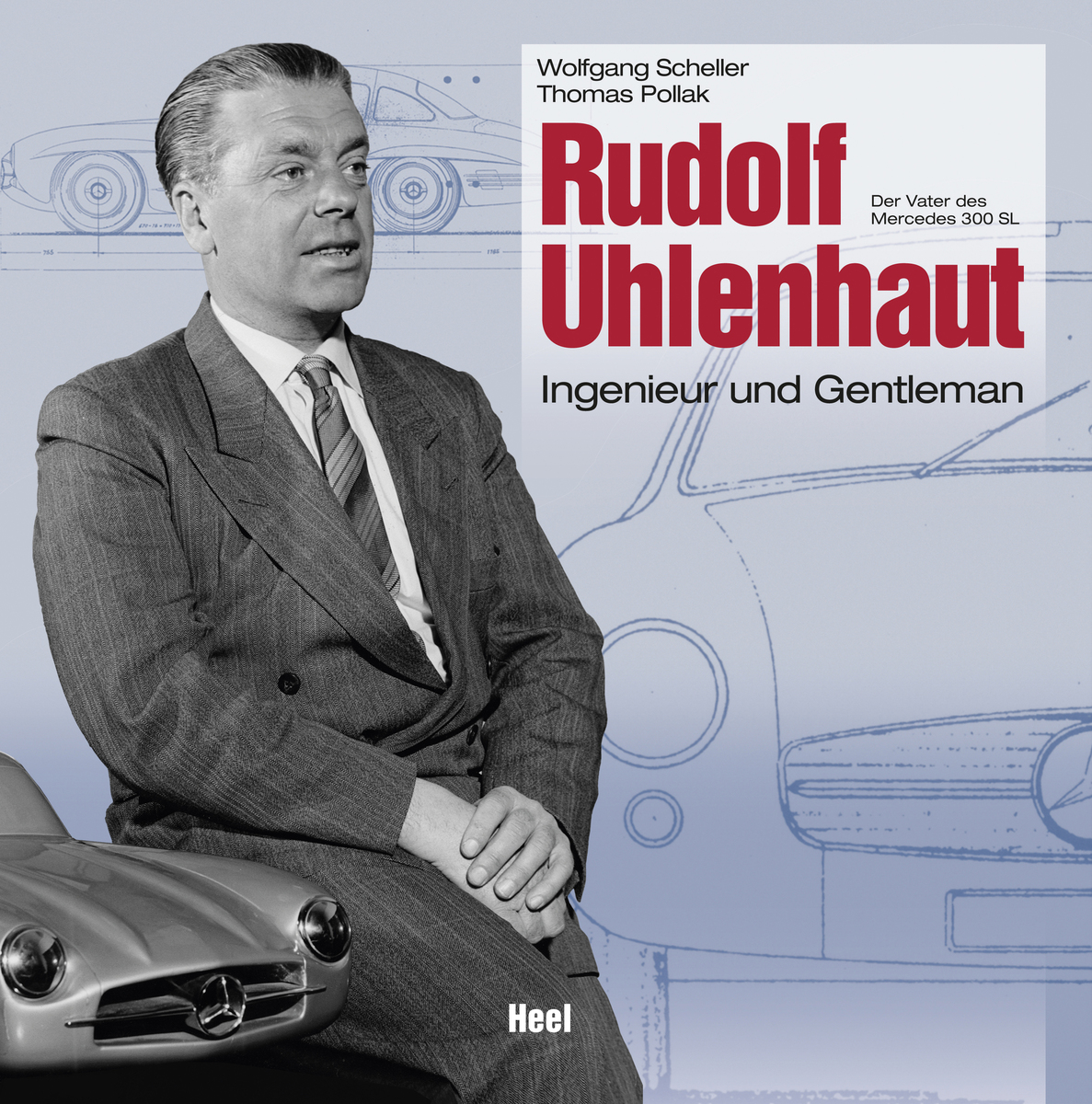

A biography of Rudolf Uhlenhaut has just been published. Of course, you will say and immediately remember the W125 from 1937, the Silver Arrow with a displacement of 5.7 liters and 570 hp, and the 300 SL. Of course, this man has a permanent place in all books on the history of Mercedes-Benz and the Silver Arrows.

Karl Ludvigsen wrote a short biography in Automobile Quarterly in 2005 (AQ 45(2005)3, pp. 100-117). But a detailed biography has not yet been published. It is thanks to Wolfgang Scheller and Thomas Pollak.

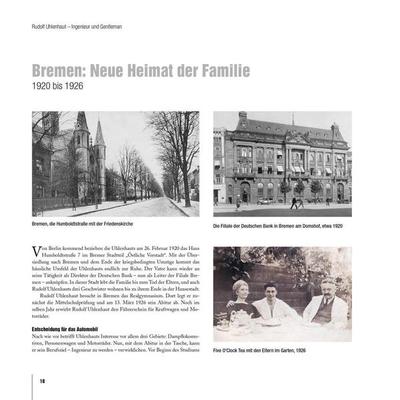

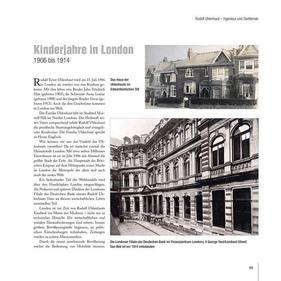

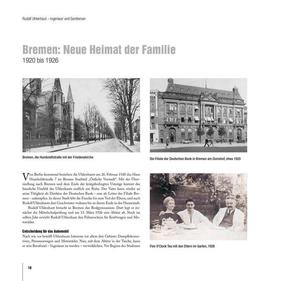

Rudolf Uhlenhaut was born on July 15, 1906, the son of the director of the Deutsche Bank branch in London and his English wife. English was spoken in the family. She had to leave England with the outbreak of the First World War. The Uhlenhauts moved via Amsterdam, Brussels and Berlin to Bremen, where his father again managed a branch of Deutsche Bank from 1921.

The most important dates in Rudolf Uhlenhaut's life are (excerpt from the chronological table on page 198):

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 15.07.1906 | Born in London |

| 1912-1926 | School education in London, Brussels, Berlin and Bremen. Abitur at Realgymnasium Bremen, then internship at Hansa-Lloyd. |

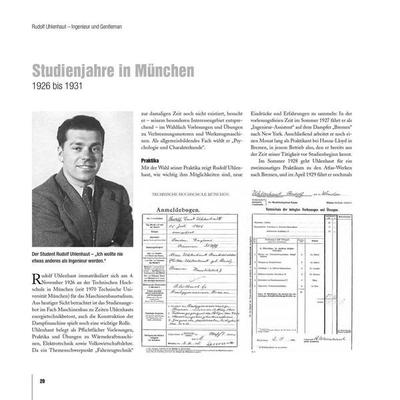

| 1926-1931 | Studied mechanical engineering at the Technical University of Munich; graduated with a degree in engineering |

| 01.07.1931 | Joined Daimler-Benz AG as an engineer and plant assistant in the testing department, Untertürkheim plant |

| 01.08.1934 | Head of the vehicle department and finishing shop |

| 01.04.1935 | Test engineer for passenger car development |

| 01.09.1936 | Technical manager of the racing department |

| 1944-1945 | Technical Manager Neupaka/Czech Republic (plant founded after the first bombing of Untertürkheim) |

| 30.04.1945 | Resigned from Daimler-Benz AG |

| 1945-1947 | Operation of a freight forwarding company in Massing/Lower Bavaria; Head of the design office of the British Army repair plant in Wetter/Ruhr |

| 01.02.1948 | Rejoins Daimler-Benz AG as a test engineer |

| from 01.04.1949 | Head of the passenger car testing department |

| from 1959 | Director of Passenger Car Development |

| 30.09.1972 | Retirement |

| 08.04.1989 | Died in Stuttgart |

Rudolf Uhlenhaut obviously always wanted to be an engineer. He followed in the footsteps of his grandfather and his brother, who both held high positions at Krupp.

Talented driver

Unlike most of his colleagues in development and testing at Daimler-Benz, Rudolf Uhlenhaut had a driver's license. Nevertheless, he never owned his own car, but always took "test drives" in the cars of the testing department, whether for business or private purposes. He rode motorcycles privately.

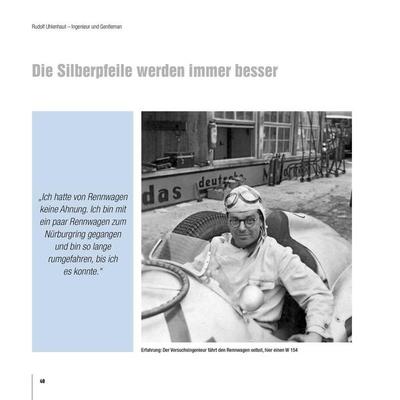

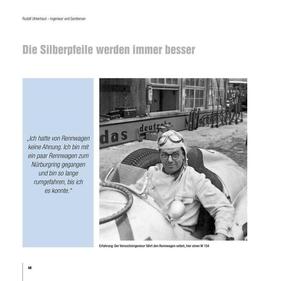

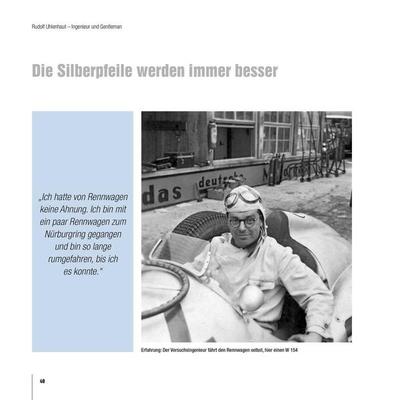

He became famous for his test drives with racing cars, where he often came very close to the times of the works drivers. He always combined his positions in testing with practical trials. From 1936, this also applied to the racing cars. After his appointment as technical director of the racing department, he took a whole day at the Nürburgring to get to know his new cars. In the evening, he noted with satisfaction that he had understood what Caracciola and his colleagues had to criticize about the car.

The right man at the right time

The establishment of a technical racing department in the course of 1936 was an expression of the desperate situation in which Daimler-Benz found itself at the time. The W25K of 1936 was no match for the Auto Union Type C. In the German Grand Prix, it even had to lag behind the Alfa Romeo 12C-36. Internally, the departments blamed each other. The young, independent and decisive Uhlenhaut was the solution. Within a few months, the W125 was created, one of the most powerful racing cars ever built. He had learned the craft by testing the Mercedes-Benz 170 V (W136).

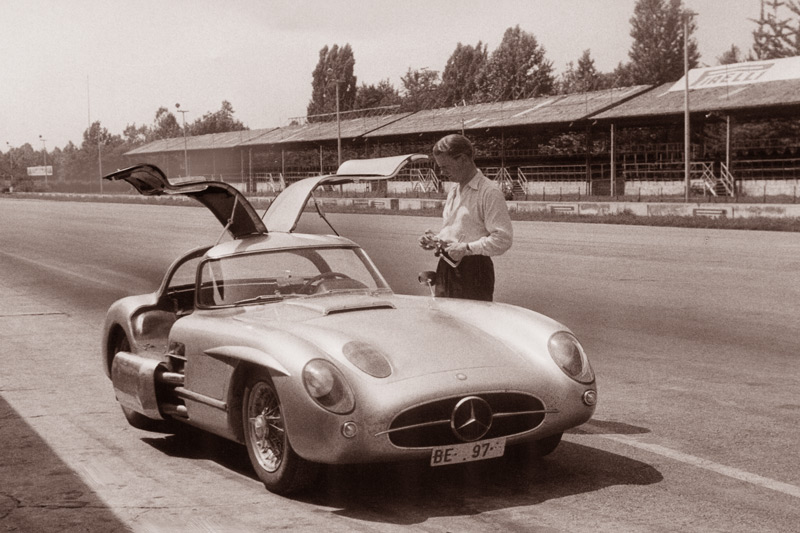

When the racing department was re-established in 1953, Rudolf Uhlenhaut was again responsible for testing. Daimler-Benz wanted to return to motor racing after the Second World War. In view of the empty coffers, a cheap solution was needed. They looked for one based on the 300 S (W188) and adopted its drivetrain. The power output in racing trim was approx. 170 hp (for comparison: Jaguar C-Type approx. 210 hp).

Lightweight construction and aerodynamics

To compensate for the power deficit, Uhlenhaut built a filigree tubular frame and placed a body optimized in the wind tunnel over it. To keep the cross-section small, he installed the engine at an angle. The result was the 300 SL (W194). The project succeeded: victory in the 24 Hours of Le Mans and in the 1952 Carrera Panamericana.

Interestingly, Uhlenhaut had already designed a tubular frame for a small racing car in 1947, i.e. before he was reinstated, but this was never realized.

One more argument

Rudolf Uhlenhaut can be mentioned in the same breath as people like Ferdinand Porsche, Colin Chapman or Adrian Newey. Unlike the others, however, he was always part of a large organization (Ferdinand Porsche had to leave the same company in 1928 after five years). In terms of the ability to drive a racing car, he can be compared to Colin Chapman. However, Porsche and Newey prove that this ability is not necessary to be able to build good racing cars. Perhaps it was also something of a unique selling point for Uhlenhaut in the large corporation. Who wanted to counter his arguments regarding handling at the limit?

Quality designer

From 1959 onwards, Uhlenhaut became much less visible to outsiders. However, as Director of Passenger Car Development, he held a key position within the Group, which he held for 13 years. Scheller and Pollak point out that Uhlenhaut was instrumental in shaping the proverbial quality of Mercedes-Benz during this time. He set the standards for development and tested the vehicles accordingly.

But during this period, new demands were also placed on the cars that had to be met: safety, consumption and the environment became key challenges in automotive engineering.

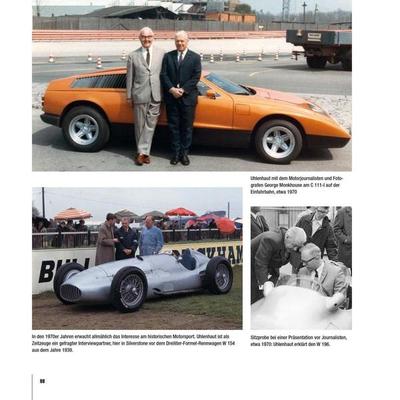

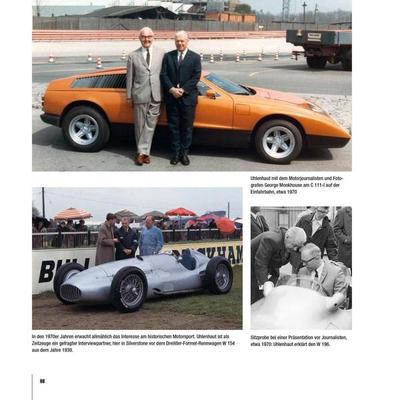

Back to the sports car with the C111

It was not until 1969 that Uhlenhaut was able to go on test drives in a sports car again with the C 111. However, the 3-disc Wankel engine had too little steam for him. Only the 4-disc engine (C 111-II) was able to warm him up. However, stability proved to be the Achilles heel of the Wankel engine and Daimler-Benz decided against series production. The C 111 was fitted with a diesel engine for further testing.

By this time, however, Rudolf Uhlenhaut had already retired.

Extensive research

Wolfgang Scheller and Thomas Pollak set out in search of Rudolf Uhlenhaut. This seems to have been difficult enough, as he did not seek publicity. In fact, his wedding date, for example, is not known and could not be ascertained. The Uhlenhaut couple's only son, Roger, gave them access to private photographs and background information. They also searched the Daimler-Benz corporate archives.

Along the timeline

The book is structured chronologically. The first chapters are dedicated to the Uhlenhaut families' years of travel from London to Bremen, their years of study in Munich and their career start at Daimler-Benz. This is followed by the chapters on work in the occupied territory, new beginnings and "On the road to success", the post-war years at Daimler-Benz and the time after retirement. These parts were edited by Wolfgang Scheller.

In between are four chapters on technology by Thomas Pollak, which describe in detail the projects Rudolf Uhlenhaut was involved in. They document the work, the solutions and also Uhlenhaut's patents (or those in which he was involved). Overall, the two parts balance each other out, with the Technology IV chapter, which provides an overview of the years after the Second World War, being the most extensive.

There are also many pictures and documents from the Uhlenhaut family's private collection; photos, drawings and reports from the company archive. A very special document is an analysis of the weak points of the W25K and the derivation of the specifications for its successor, i.e. the W125.

The two sides of the Uhlenhaut

The content is supplemented by two cross-sections, each on two pages, which describe Rudolf Uhlenhaut as a test engineer and as a gentleman. They succinctly and precisely reflect the two central themes of the book and are suitable as an introduction to the book as a whole, in which the details are then provided.

If one compares the biography by Scheller/Pollak with that of Ludvigsen, a few differences become apparent. Ludvigsen, for example, reports that Uhlenhaut, after returning from a long vacation to reduce his remaining vacation time shortly before retiring, found a person he did not know in his old office and was assigned a new office at the end of the corridor. Uhlenhaut was very disappointed by this procedure. Ludvigsen describes it as shabby. Scheller/Polak do not use such harsh words. Ludvigsen obtained his information primarily from Erich Waxenberger, Hans Liebold and Kurt Obländer, Uhlenhaut's employees. He also knew Rudolf Uhlenhaut personally. Scheller/Pollak refer to the designer Josef Müller, who writes about Uhlenhaut in his memoirs, and Kurt Obländer. It is therefore worth consulting Ludvigsen's short biography.

Wolfgang Scheller and Thomas Pollak paint a picture of a team worker who greatly valued direct contact with his employees and always discussed things on an equal footing. The authors attribute this to his time as a trainee in England, where he learned to take teamwork for granted. This also included English understatement. Just a gentleman.

As a technician, he was an outstanding analyst who was able to identify and quickly rectify shortcomings, particularly in driving practice, and they describe him as an optimizer, as opposed to an innovator, although the boundary remains vague, of course.

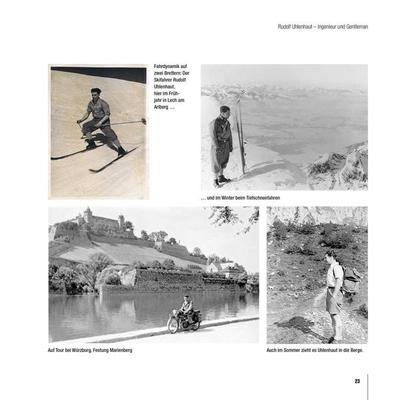

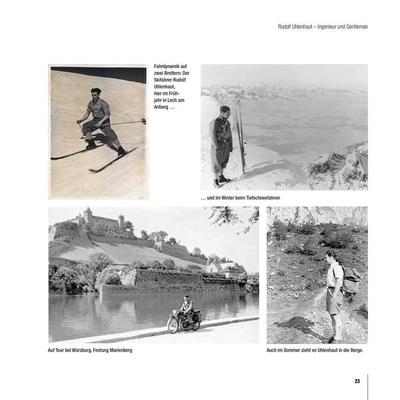

Technology at the center

It is also the image of a technician who is not interested in politics and has no ambitions to become a board member. Uhlenhaut appreciates working in a company where technicians enjoy a high reputation and there is enough money for development. But he also appreciates the amenities such as traveling around the world and regular vacations so that he can practice his beloved sport of skiing or engage in sporting activities in general. Kurt Obländer told Karl Ludvigsen that he had never seen Rudolf Uhlenhaut frustrated (in a global corporation and in a central function, nota bene).

The book is of course intended for readers with an admiration for Mercedes-Benz. It provides a justification for the high quality of the vehicles and describes the people and the culture in which the necessary awareness could develop. It is also a look behind the scenes of the racing successes with the Silver Arrows in the 1930s and 1950s. Of course, Rudolf Uhlenhaut is always at the center. It is a biography, company history and technical history in equal measure and is therefore also of interest to anyone with a general interest in automotive history. It is a contribution to the question of how technology came into being (back then).

Bibliographical information

- Title: Rudolf Uhlenhaut: Engineer and Gentleman - The Father of the Mercedes 300 SL

- Author: Wolfgang Scheller & Thomas Pollak

- Language: German

- Publisher: Heel

- Edition: 1st edition 2015

- Size/format: hardcover with jacket, 255 x 255 mm, 200 pages

- ISBN-13: 978-3-9584315-0-8

- Price: EUR 49.95

- Order/buy: Online at Heel-Verlag, online at amazon.deor in well-assorted bookstores